Role of the minerals sector and challenges to inclusive growth

Mongolia’s minerals sector has been the main driver of the country’s rapid economic growth: it currently accounts for 18.6 per cent of GDP and approximately 80 per cent of exports. In recent years, the sector has been responsible for over 70 per cent of new foreign direct investment (FDI) into Mongolia. It is also increasingly important to the state budget, accounting for approximately 30 per cent of government revenues.

Economically, Mongolia has become a mining nation, with significant ramifications for the country’s socio-cultural fabric. And while the country ranks among the top 10 countries in various mineral resources, policy-makers have yet to determine how best to leverage this wealth to advance national prosperity in a balanced and ultimately sustainable way. Although there are many solutions and diverse suggestions drawn from international experience and covering a range of outstanding issues, from institutional capacity to the management of resource rents, there is strength in the argument that Mongolia needs a more tailored approach which takes sufficient account of its unique location and developmental trajectory.

An approach that is tailored to Mongolia’s unique situation may be in order: since 2009, the Mongolian economy has tripled in size, largely due to tremendous investment in its copper and coal industries. Unfortunately, there is scant evidence to show that this staggering economic growth has been accompanied by the institutional reform that is essential to underpin the sustainability of that growth. Key indices, among them economic competitiveness rankings, governance indices and studies of corruption during a similar period have not improved to the extent that was hoped for.

In fact, the boom-and-bust nature of mining, coupled with Mongolia’s vibrant democracy, has created a number of new challenges for the country. Mongolia’s parliamentary elections of 2008 and 2012 were accompanied by protectionist undertones, as well as promises of cash handouts designed to win over voters who felt they had not sufficiently benefited from mining-led economic growth. This behaviour served to exacerbate state budget deficits and further damage the country’s balance of payments. This in turn fuelled inflation and put increased pressure on the national currency, the togrog. Ultimately, this worsened macroeconomic imbalances and served to hinder genuine efforts to diversify Mongolia’s economy and build inclusive growth.

For the Mongolian minerals sector to function efficiently and promote sustainable development, reforms should be founded on three pillars: (i) enhancing institutional capacity; (ii) building public support; and (iii) improving government support for investment. What follows is a discussion of each of these pillars individually.

CHART 3: MINING SECTOR IS THE ENGINE OF MONGOLIA'S ECONOMIC GROWTH

Note: GDP = Gross domestic product. FDI = Foreign direct investment

CHART 4: COMPOSITION OF MONGOLIA'S GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT BY SECTORS

CHART 5: MONGOLIA'S DEPENDENCE ON MINERAL RESOURCES

Enhancing institutional capacity

After nearly seven decades of one-party socialist rule, Mongolia peacefully transitioned to a semi-presidential parliamentary democracy in 1990. At present, the parliament is the main policy-making body for the minerals sector and therefore exerts the greatest influence over its direction. It is not the only decision-making body, however: the government is able to enact regulations and also exercises control over the determination of areas which are open for exploration. The Ministry of Mining, meanwhile, is in charge of drafting policy and managing its two regulatory agencies: the Mineral Resource Authority of Mongolia (MRAM) and the Petroleum Agency of Mongolia (PAM). In addition to their respective regulatory duties, MRAM is responsible for the issuance of exploration and mining licences, and PAM is responsible for the issuance of oil and gas exploration licences and the execution of production-sharing agreements.

In 2014, the government initiated the amendment of several existing laws with the aim of liberalising the minerals sector and reducing bureaucracy related to permitting and contract negotiation. While both domestic and foreign investors have welcomed these improvements, low international price levels for Mongolia’s major commodities have meant that the country will have to wait for capital investment to return.

Among the goals of the latest Minerals Policy is an increase in the volume and quality of information in the state geological database, which the government plans to accomplish through the implementation of standard international surveying methods and mineral classifications. In late 2014, Mongolia joined the Committee for Mineral Reserves International Reporting Standards (CRIRSCO) and, as a result, adopted the Australasian Joint Ore Reserves Committee (JORC) Code. The JORC Code governs the classification of exploration results, mineral resources and ore reserves. (Mongolia had previously used an old classification system developed by Soviet-era geologists.) Experts hope that bringing the country’s geological database in line with international standards and updating it annually will encourage increased exploration by private companies.

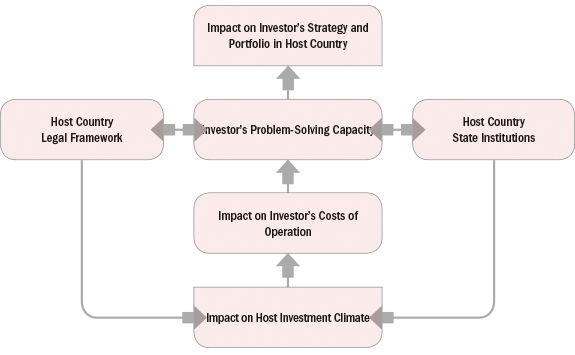

While there has not yet been any comprehensive study of the institutional capacity in Mongolia’s minerals sector, sources such as the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index; the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators; the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report; and consulting firm Behre Dolbear’s rankings of top countries for mining investment all suggest that Mongolian government institutions perform poorly in supporting business and enabling sustainable investment. While the government has taken steps with the Minerals Policy to improve its ability to work with the private sector, currently available data indicates that it still has a long way to go.

CHART 6: MONGOLIA'S GROWTH IN GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE AND REVENUE

Building public support

Further complicating matters is the fact that Mongolia’s mining industry is facing an identity crisis. The country is home to such world-class projects as the Oyu Tolgoi (OT) and Erdenet copper mines, as well as numerous medium- and small-scale mines, including some that are illegally operated by artisanal miners. These three mine classes are currently in contention in the public imagination for the defining image of the sector.

Large mines such as OT – often termed “mega projects” – are generally foreign-invested and employ world-class safety standards and environmental practices. Their performance has a huge impact on the Mongolian economy. As a result, they are often featured in international news stories, which in turn greatly influence the outside perception of the Mongolian government and the state of the country’s minerals sector as a whole.

Medium-scale mines, meanwhile, are generally not covered in international news stories nor do they meet international standards – although they are improving in this regard. This is in contrast to illegal, small-scale mines operated by artisanal or so-called “ninja” miners. Although artisanal mining is seasonal and not closely monitored by the government, estimates place the number of workers employed by these small mines somewhere between 17,000 and 40,000. Despite government efforts, these mines are generally beyond the reach of workplace-safety and environmental regulatory authorities.

Because of the environmental damage caused by irresponsible miners – particularly artisanal miners – and because resource rents often do not trickle down to the local level, many small communities are reluctant to support mining. Public polls by the Ministry of Mining have shown that respondents generally do not believe that the minerals sector is benefiting the country.

However, surveys by the non-governmental organisation Sant Maral Foundation suggest that there has been a shift in national thinking about resource rents: an increasing number of respondents have stated they prefer long-term investment to direct transfers in allocation of resource rents. According to these surveys, the Mongolian public also largely continues to support significant state participation in the development of mineral deposits deemed strategically important by the state, as they see this as a way to ensure that the Mongolian people benefit from mining.

The opportunistic rhetoric of populist politicians, coupled with the occasional misconduct of foreign and domestic mining companies alike, has in recent years had a chilling effect on the development of Mongolia’s minerals sector. Ultimately, only educated voters can assist in creating a political environment that enables the formulation of government policy geared towards effective regulation and sustainable development. To do this, policy-makers must acknowledge the degree to which the country’s socialist past and semi-nomadic traditions shape policy debates, and adopt a communication strategy that allows for a constructive national discussion of the role of mining in Mongolia’s new economy.

Improving government support for investment

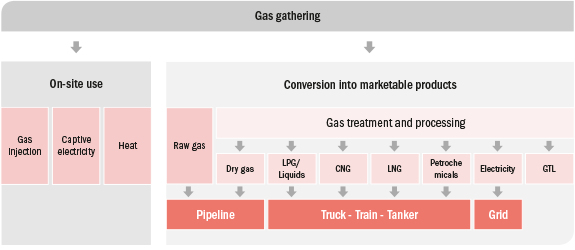

At the core of the Minerals Policy’s numerous objectives is the need to foster the development of a responsible, transparent mineral extraction and processing industry that is sustainable, export-oriented and compliant with modern international standards.

With regard to the development of strategically important mineral deposits, the state’s current objective is to develop better cooperation with the private sector, while also improving control and oversight of these deposits. While the Minerals Policy does not state how this will be achieved, it does seek to ensure efficient monitoring of mining operations by state and local authorities. This includes monitoring the levying of appropriate fees and charges, and ensuring that charges are not duplicated by different levels of government.

The Minerals Policy additionally aims to increase Mongolia’s ability to conduct secondary processing of minerals and engage in other value-added activities. The government hopes to accomplish this through the introduction of tax and other financial incentives for projects such as coal-concentrate, coking-coal and chemical plants. Coal-fired power plants and plants that extract liquid fuel or gas from brown coal and fuel from oil shale are also eligible.

The Minerals Policy also seeks to create conditions that will allow both investors and local communities to better understand the social and economic impact of a mining project through public presentations before the commencement of mining operations. This is in line with the current Minerals Law, which states that a transparent, inclusive local development agreement should be formed between the investor and the local community before project development.

Despite its adherence to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), Mongolia continues to struggle in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking 80th out of 175 countries in 2014. (However, this was an improvement from 2012, when it ranked 95th.) One of the challenges for the country in the coming years will be to create greater openness in agreements between public-sector agencies and officials and private companies.

Human capital development is also crucial to ensuring that Mongolia is an attractive jurisdiction for mining companies. Despite the country’s high adult literacy rates, private companies surveyed by the World Economic Forum (WEF) frequently cite an inadequately educated workforce as the main barrier to doing business in Mongolia. Ensuring that workers are sufficiently skilled is particularly critical for the success of the minerals sector, which requires highly qualified specialists capable of carrying out exploration or production operations in the country’s often-harsh climate. To this end, the Mongolian parliament recently ratified the International Labor Organization’s Safety and Health in Mines Convention, as prescribed by the Minerals Policy.

The Minerals Policy also calls for the establishment of a Policy Council in which the views of the government, investors, professional associations and the public are represented. Conceivably, the Policy Council would support the implementation of the Minerals Policy and make recommendations as to how it might be refined. (This would be similar to the Policy Council created by the Ministry of Mining in 2014, which has worked to improve dialogue between the government and private sector stakeholders.) Were it to be created, the Policy Council would also be tasked with safeguarding the legal stability of the Minerals Policy during the 2016 parliamentary elections.